We live immersed in plastic. It can be found everywhere; we see it in the seas, dragged by the waters of our rivers, even scattered on mountain peaks or in the countryside that we still consider uncontaminated… Now we are beginning to realize that we eat and drink it. And we can do very little about that, if things do not change. In fact, what comes from our food, spices, water and, as shown by the first analysis carried out by Il Salvagente on 18 industrial beverages, from cola to orangeade, from lemonade to iced tea, we cannot see it with the naked eye nor can we avoid it.

The danger, in this case, has a specific name and a scientific definition, even though researchers and analysts have only recently started to look into it, and a level of risk that is still largely unknown. It is called microplastic, this is the definition of solid particles that are insoluble in water, even with dimensions that are much smaller than 5 millimetres. So small it is hardly distinguishable and perhaps for this very reason just as, if not more, insidious than the larger fragments from which it comes. Which, needless to say, are the most commonly used polymers, such as polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, polyamide, polyethylene terephthalate, polyvinylchloride, acrylic, polymethyl acrylate.

For some years now, those who look for it, regardless of what they are analyzing, find it. It is found in the fish fillets we consume, where they accumulate in incredible quantities, in seafood, in sea salt, in water (from rivers and taps, even in mineral water). It is even present in products like honey.

It is inevitable, therefore, that it would also be detectable in the soft drinks that the monthly consumer guide magazine sent to the Maurizi Group laboratories. If anything, it is hardly surprising that none of the kinds of tea, cola, lemonade, orangeade, or tonic water under analysis were saved.

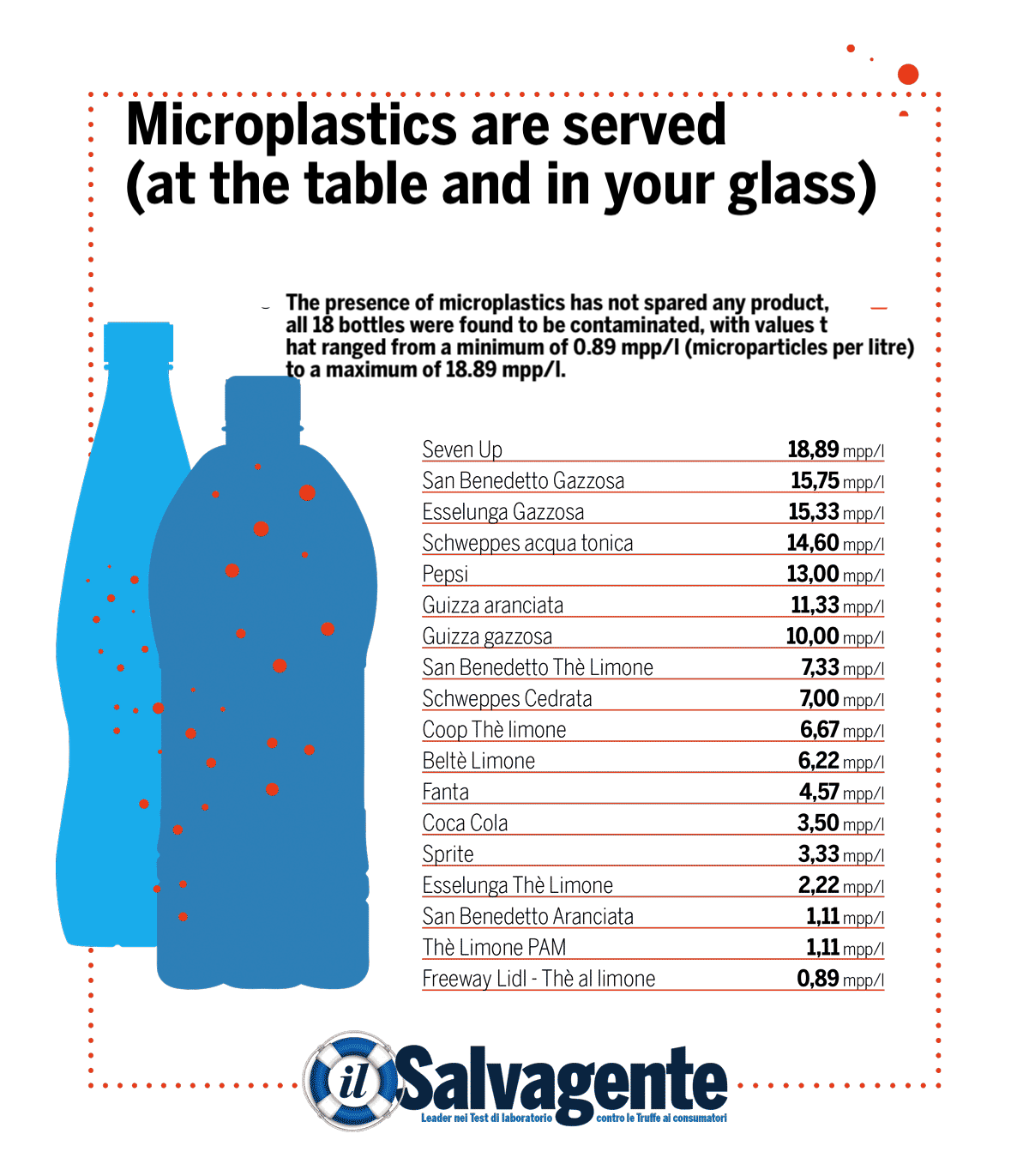

Microplastics are served (at the table and in your glass)

Seven Up, Pepsi, San Benedetto, Schweppes, Beltè, Coca-Cola, Fanta, Sprite are just some of the brands to end up under the microscope and – with a slight surprise – all gave an unambiguous response: the presence of microplastics has not spared any product, all 18 bottles were found to be contaminated, with values that ranged from a minimum of 0.89 mpp/l (microparticles per litre) to a maximum of 18.89 mpp/l.

How they looked for it

To make the measurements, the laboratory chose to use the method used by the Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences of the State University of New York at Fredonia, the very university that published the study on 253 types of mineral waters last March on orbmedia.org.

That work and several previous studies have shown how the use of Nile red can enable the rapid detection and quantification of microplastics given its characteristic absorption selectivity and fluorescent properties. This stain preferentially binds to polymeric materials rather than to organic materials (algae, wood and feathers) and other inorganic environmental contaminants.

It can be used for rapid detection of microplastics without the need for additional spectroscopic analyses (thus reducing the time required to analyze an environmental sample) and it is all that is needed to identify a polymer particle. Despite being challenged by some of the industrial brands in the US study, who put forward the possibility of false positives, this testing method remains one of the most advanced currently available. In addition, beyond the inevitable polemics that will arise from Il Salvagente’s analysis, it must be said that results obtained in all tests on food always show the presence of microplastics.

A ‘vehicle’ for poisons

Where does it come from and what are the dangers we can expect from this invisible but constant invasion of fragments that end up in our food?

There are no easy or univocal answers. If, just to give an example, cosmetics have had, and still have, a fundamental role in the origin of microplastics, as they have been inserted into cosmetics products on purpose (one of the many reasons is to give the scrub effect), today the chain of this contamination appears much longer and more complex. Just as the chain of effects seems increasingly probable, at least judging from initial studies, however controversial they might be.

Seen from Brussels, for example, the question of plastic particles that we ingest is not considered as so worrying: “According to current knowledge, it is unlikely that ingestion of microplastics ‘per se’ is an objective risk to human health”, writes the European Union.

Seen from Helsinki, from the headquarters of the European Chemical Agency (the ECA), the perspective is different. “Some of the additives or organic contaminants that are added to plastics can be toxic”, the agency stated in black and white in a document a few months ago. And it is not just Finnish scientists to be concerned about this. There are numerous studies – all very recent, seeing that the issue is relatively new – that show how microplastics can become a convenient ‘vehicle’ for toxic substances, concentrating and transporting pollutants such as bisphenol, some phthalates, pesticides and other carcinogenic molecules as well as interfering with the endocrine system.

And it is not just the dangers of the substances added in the processing of plastic, but also of those that it collects as it travels during its long life. According to the French agency Centre national de la recherche scientifique, particles of less than 5 millimetres have the capacity to “bind to organic pollutants in the environment such as PCBs, dioxins or PAHs” and pathogenic microorganisms. There are not sufficient studies to quantify the impact on humans, but the risk is already evident: ingesting particles that are invisible to the naked eye that, once in our organism, release their load of poisons.

“We don’t want to find ourselves in the same dramatic situation as we did with asbestos”, Matteo Fago explains, “a material considered safe and inert for many years before it was discovered, too late, how serious and extensive the damage it had produced on human beings was.”